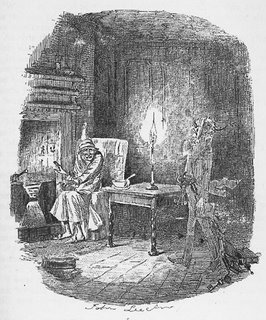

It's got apparitions, transformations and all manner of scenes from the frenzied delights of a Christmas ball to ghostly goings-on in a graveyard.

It's got apparitions, transformations and all manner of scenes from the frenzied delights of a Christmas ball to ghostly goings-on in a graveyard.A Christmas Carol might almost have been written for the stage and it certainly has been on the stage at sometime or other for pretty much every one of its 163 years.

Take this Christmas [2006], for example: there will be revivals of Leslie Bricusse’s all-singing version and Christopher Gable’s all-dancing production; with famous former-Fagin, Ron Moody taking on a new Dickensian persona in Swansea as Ebenezer Scrooge and Michael Barrymore (above) reprising his portrayal of the role on tour.

It was in December 1843, that Dickens - angered by the terrible poverty of his day - published this little 'ghost story of Christmas', recounting the reformation of a mean-spirited man for whom December 25th and all associated with it is nothing more than "HUMBUG!" Though scarcely more than a novella, Dicken's Carol is crammed with memorable characterisations - living and spectral - and a series of rich descriptions of Christmas traditions and celebrations.

Within two months, there were no less than eight dramatised versions of A Christmas Carol being simultaneously presented on the London stage.

In order to avoid confusion, the titles were different - but only just! One was called A Christmas Carol, or the Miser's Warning; another A Christmas Carol, or Past, Present, and Future; a third A Christmas Carol, or Scrooge the Miser's Dream, or, The Past, Present, and Future...

One of the first performers to portray Scrooge was the celebrated Victorian actor, O. Smith, whose performance was described by Dickens as “drearily better than I expected”, adding that he found it “a great comfort to have this kind of meat underdone” - something which cannot be said of all his successors!

2006’s Scrooge’s - whether professional or amatuer - are the latest in a long line of performers to play the “squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner” and distinguished humbugs have included veteran thespians Bransby Williams and Seymour Hicks who both began by playing the part in legitimate theatrical productions before transforming their performances into solo music hall turns and then ending up among the first screen Scrooges - succeeded by the likes of Alistair Sim (for many the greatest of Scrooges), Albert Finney, George C Scott and Michael Caine in the much-loved musical version The Muppet Christmas Carol.

There has been an Ebenezer Scrooge for every possible taste from Anthony Newley to Anton Rodgers; from the senior partner of Steptoe and Son, Wilfred Brambell, to Star Trek's Jean-Luc Picard, Patrick Stewart (right); and employing every conceivable medium from a mime performed by Marcel Marceau to an opera sung by Sir Geriant Evans.

There has been an Ebenezer Scrooge for every possible taste from Anthony Newley to Anton Rodgers; from the senior partner of Steptoe and Son, Wilfred Brambell, to Star Trek's Jean-Luc Picard, Patrick Stewart (right); and employing every conceivable medium from a mime performed by Marcel Marceau to an opera sung by Sir Geriant Evans.'Scrooging' has long been a popular pastime among knights of the theatre: Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson and Alec Guinness all did it on radio, Michael Hordern did it on television and John Gielgud on record. Others who have read the story on disc, tape and CD include Geoffrey Palmer, Richard Wilson, Ronald Coleman, Vincent Price and Leonard Rossiter.

In America, where A Christmas Carol is equally - perhaps even more - beloved, Dickens' stony-hearted skinflint was portrayed or radio, for many years, by Lionel Barrymore and Orson Welles and on other occasions and in a variety of media by Basil Rathbone, Frederick March, Walter Matthau, Kelsey Grammer, Mr Magoo and Donald Duck's penny-pinching uncle, Scrooge McDuck!

From the outset, dramatists have tinkered with the original text: from small embellishments such as giving Scrooge's nephew, Fred, the surname 'Freeheart', to the invention of a sinister character called 'Dark Sam' who added to the Cratchit family's problems by stealing Bob's scant wages. One particularly free dramatization, Old Scrooge, staged in 1877, ended by reuniting the reformed miser with his lost love, Belle, who conveniently turns out to be Fred's wife's widowed mother!

Some of the more bizarre curiosities - Vanessa Williams as self-centered pop-star, Ebony Scrooge; Jack Palance as Ebenezer, a Western card-cheat and gunfighter; or Bill Murray as Frank Cross, the cynical TV executive who gets Scrooged - serve to indicate the extent to which Dickens' story has become part of popular mythology, a folk tale or fairy story which is perennially retold and reworked in the telling.

So well do we know - and love - Dickens' story that it's characters have had several sequels written about them with several amusing speculations on what might have happened if Ebenezer Scrooge had subsequently relented of his Christmas conversion and had gone back to his old miserly ways and some alarming accounts of how the angelic Tiny Tim might have turned out not so virtuous when he grew up and inherited Scrooge's business! Why, there is even a Jewish spoof on the story entitled Hanukkah, Schmanukkah!

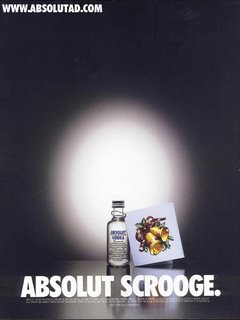

Dickens' characters have been employed by several generations of political cartoonists from Punch's John Tenniel, who depicted Prime Minister William Gladstone as Scrooge, to Gerald Scarfe who drew the Ghost of Margaret Thatcher haunting a terrified John Major. They have also found their way into various advertising campaigns for, among other products, Hamlet cigars, Heineken lager and Absolut vodka.

In fact, so well known is A Christmas Carol that even people who have never read it, actually believe they have! Say the word “Humbug!” and someone will think of Ebenezer Scrooge; utter the phrase: “God bless us, every one!” and people at once recall the words of Tiny Tim.

Small wonder that William Makepeace Thackeray, reviewing the book in 1843, wrote: “It seems to me a national benefit, and to every man and woman who reads it a personal kindness.”

One hundred and sixty-three years on, there seems no reason to quibble with that verdict.